The Greek tablet of the Persepolis Fortification archive

Inscription

Οἶνο-

ς δύο

II

4 μάρις,

Τέβητ.

Wine, two (II) maris, (month of) Tebet.

Inscription Credits

Ancient text after Rougemont, G. 2012. Inscriptions grecques d’Iran et d’Asie centrale, avec des contributions de Paul Bernard. Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum, part II, vol. I.1. London: no. 54. Reproduced by permission of Georges Rougemont and the Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum.

Comment

This is the only known record inscribed in Greek of the so-called Persepolis Fortification archive, a group of tens of thousands of tablets and fragments recovered from two rooms of a bastion in the fortification wall at the northeastern corner of the Persepolis platform. The group consists, in the main, of Elamite cuneiform documents, but there are also hundreds of Aramaic documents in alphabetic script, some 5000 uninscribed, sealed, tablets, and a small number of unica texts, like the Greek tablet, in Old Persian, Babylonian, Phrygian, and Egyptian Demotic. The archive’s records deal essentially with the storage and distribution of edible commodities and management of livestock in the Persepolis administrative province, which roughly coincided with modern Fārs. Many of them, dated by regnal year, span the period between the 13th and the 28th regnal year of Darius I, or 509-493 BC (Henkelman 2008: 123-125; Stolper 2025).

The Greek text was initially published by Richard T. Hallock (1969: 2), whose copy of the original is featured in subsequent editions (e.g., Balcer 1979: 280 [SEG 29 (1982) no. 1586]; Canali De Rossi 2004: no. 230; Rougemont 2012: no. 54). The tablet is further commented on in a number of treatments of the archive’s documents (e.g., Stolper 1984: 304; Stolper and Tavernier 2007: 3; Azzoni et al. 2017, Azzoni et al. 2019: 3-4), and commentaries that relate to ancient Greek presence in Iran (e.g., Lewis 1977: 12-13; idem 1985: 107-108; Boardman 2000: 133; Rollinger and Henkelman 2009: 342-343; Pompeo 2015: 157-169, eadem 2017). The most recent study considers new information about the seal applied on the tablet that could support an identification of the writer of the Greek inscription with a named functionary of the Persepolis administration (Aperghis and Zournatzi 2023, with comprehensive references to the earlier literature).

The tablet’s various features leave little room for doubting its functionality in an Achaemenid administrative environment. Its form (tongue-shaped with two string holes) and size comply with those of other transaction records of the Fortification archive (the so-called memoranda, Hallock 1969: text categories A-S), which usually deal with single commodity transfers; the small amount of wine and month notation recorded on the tablet refer us, in particular, to the archive’s numerous ration texts. The two seal impressions —on the flattened left edge and the reverse, respectively, of the tablet— are equally characteristic of Persepolis bureaucratic practice, in which seals served as tokens of jurisdiction and agency. Other references to the archive’s ‘system of information and recording’ (Stolper and Tavernier 2007: 4) are provided by the wording of the text. Its terse format and lack of syntax find parallels among the archive’s Aramaic documents which, in contrast to the usually more detailed formulations of Elamite transaction records, sometimes record merely a commodity, personal name, title, month name, or year number (e.g., Azzoni 2017: 456). Also like the Aramaic documents, the Greek document gives a Babylonian - Aramaic month name (Ṭebēt - Ṭbt, corresponding to December/January), instead of the Elamite and Iranian ones that are regularly featured in the Elamite Fortification records (e.g., Stolper 1984: 304 n. 12). Μάρις, attested as marriš in the Elamite tablets, was presumably borrowed from Iranian (Schmitt 1989, with attestations of the term in Greek texts); it is the liquid measure for wine and beer in the administrative documents found at Persepolis, equivalent to about 10 liters (Bivar 1985: 610-639). The Greek numeral δύο (‘two’), indicating the quantity of μάρις, is glossed with two vertical strokes, a numerical mark of the tallying sort known from Archaic period and later Greek contexts (Aperghis and Zournatzi 2023: 7 n. 20), and also attested as a gloss for ‘two’ on an Aramaic Fortification tablet (PFAT 047: Pompeo 2015: 162 and fig. 7, eadem 2017: 14-15). As Matthew Stolper and Jan Tavernier (2007: 20) observed, ‘even the word for the commodity, oinos, “wine,” is a Kulturwort, perhaps recognizable to an Aramaic speaker … To understand [this text] required no real knowledge of the Greek language … only the skills of literacy’.

Elusive for long, the specific context within which this document was drafted can be placed into closer focus, thanks to information made available by the currently ongoing Persepolis Seal Project, initiated by Margaret Root and Mark Garrison, and Persepolis Fortification Archive Project. The Greek tablet’s two seal impressions were made, both of them, by seal PFS 0041 (Garrison and Root 2001: 6; Aperghis and Zournatzi 2023: 5 fig. 3), which is exclusively attested otherwise on Elamite records of the archive as a supplier’s seal, and is associated with a named official of the Persepolis storehouses system: the wine supplier Ibaturra. This supplier was responsible for a number of storehouses in a district to the northwest of Persepolis, in the area of modern Fahlīān (Henkelman 2008: 380, 501-503, with initial reference to the Greek tablet as bearing Ibaturra’s seal on p. 502 n. 1163) or, more probably, beyond it, towards Behbahān and Rāmhormoz (Aperghis and Zournatzi 2023: 12 n. 47, 16-17 n. 63), in the 21st, 22nd, and 23rd regnal year of Darius I, or 501/500, 500/499, 499/498 BC. To judge by the seal overlap with the Elamite records, the wine transaction recorded on the Greek tablet fell within the purview of Ibaturra, and must have been drafted in this supplier’s district around 500 BC.

Prior to this knowledge, the writer of the tablet was variously perceived as a Greek speaker, who had ‘a certain role, however modest’ within the Persepolis administrative network (Rollinger and Henkelman 2009: 342-343; see also earlier Lewis 1977: 13, idem 1985: 107), a Greek who ‘was bilingual; a dragoman in the Persian court’ (Balcer 1979: 280), or, perhaps, a member of a group of Greek workmen engaged in the Persepolis region, integrated in the local system (like an attested ‘scribe/secretary’ of an Egyptian group with an Egyptian sounding name, mentioned on an Elamite tablet probably from Achaemenid Susa: Jones and Stolper 1986: 247-253). As argued recently, the presently available information about seal PFS 0041, and the manner of its application in this instance allow a hypothesis that the Greek speaker, who drafted the text, was none other than the wine supplier Ibaturra himself. In Persepolis bureaucratic and archival practice in general, the suppliers and recipients of commodities were normally recognized through impressions made on the tablets by their respective seals (e.g., Hallock 1977, Aperghis 1999, Henkelman 2008: 129-135, Root 2008, Garrison 2017). In the standard sealing procedure attested in the Elamite records of the archive, the double application of PFS 0041, as the only seal used, on the Greek tablet could serve to denote Ibaturra’s jurisdiction and agency as, at once, supplier and receiver; and the wine ration recorded may well have been appropriate for Ibaturra’s rank as responsible for a district encompassing several storehouses. The simultaneous absence of any other identifying information, apart from Ibaturra’s seal, would more probably indicate that the wine was for this individual’s own use. And in this case, one cannot preclude that, in the absence of a regular Elamite scribe, the ration was recorded by this storehouse official himself, and that —regardless of difficulties in finding a suitable Greek etymology for his name— he could be a native Greek speaker. (For detailed presentation of the argument, see Aperghis and Zournatzi 2023; for an earlier discussion of possible instances of Greeks in the Persepolis administration, see, e.g., Rollinger and Henkelman 2009.)

Bibliography

Aperghis, G. G. 1999. ‘Storehouses and systems at Persepolis: evidence from the Persepolis Fortification tablets.’ Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 42: 152-193.

Aperghis, G. G. and Zournatzi, A. 2023. ‘The Greek tablet (Fort. 1771) of the Persepolis Fortification archive.’ ARTA 2023.001, available online at http://www.achemenet.com/pdf/arta/ARTA_2023_001%20Aperghis%20Zournatzi.pdf

Azzoni, A. 2017. ‘The empire as visible in the Aramaic documents from Persepolis.’ In Jacobs, Henkelman and Stolper 2017: 255-268.

Azzoni, A., Dusinberre, E. R. M., Garrison, M. B., Henkelman, W. F. M., Jones, C. E. and Stolper, M. W. 2017. ‘Persepolis administrative archives.’ Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, available at https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/persepolis-admin-archive/ (published June 9, 2017).

Balcer, J. M. 1979. ‘Review of J. Hofstetter, Die Griechen in Persien.’ Bibliotheca Orientalis 36: 276-280.

Bivar, A. D. H. 1985. ‘Achaemenid coins, weights and measures.’ In Gershevitch, I. (ed.), The Cambridge History of Iran, vol. 2: The Median and Achaemenid Periods. Cambridge: 610-639.

Boardman, J. 2000. Persia and the West: An Archaeological Investigation of the Genesis of Achaemenid Persian Art. London.

Canali De Rossi, F. 2004. Iscrizioni dello Estremo Oriente Greco. Un repertorio. Inschriften griechischer Städte aus Kleinasien 65. Bonn.

Garrison, M. B. 2017. ‘Sealing practice in Achaemenid times.’ In Jacobs, Henkelman and Stolper 2017: 518-580.

Garrison, M. B. and Root, M. C. 2001. Seals on the Persepolis Fortification Tablets, vol. I: Images of Heroic Encounter, with seal inscription readings by C. E. Jones, Parts I-II. The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publications 117. Chicago.

Hallock, R. T. 1969. Persepolis Fortifications Tablets. The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publications 92. Chicago. Also available online at https://isac.uchicago.edu/sites/default/files/uploads/shared/docs/oip92.pdf . For the archive’s documents, see also the Persepolis Fortification Archive Project database at the Online Cultural and Historical Research Environment (OCHRE) of the Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, https://isac.uchicago.edu/research/projects/persepolis-fortification-archive

——. 1977. ‘The use of seals on the Persepolis Fortification tablets.’ In Gibson, McG. and Biggs, R. D. (eds.), Seals and Sealing in the Ancient Near East. Bibliotheca Mesopotamica 6. Malibu, CA: 127-133.

Henkelman, W. F. M. 2008. The Other Gods Who Are. Studies in Elamite-Iranian Acculturation Based on the Persepolis Fortification Texts. Achaemenid History XIV. Leiden.

——. 2017. ‘Imperial signature and imperial paradigm: Achaemenid administrative structure and system across and beyond the Iranian plateau.’ In Jacobs, Henkelman and Stolper 2017: 45-256.

Jacobs, B., Henkelman, W. F. M. and Stolper, M. W. (eds.) 2017. Die Verwaltung im Achämenidenreich — Imperiale Muster und Strukturen / Administration in the Achaemenid Empire — Tracing the Imperial Signature. Classica et Orientalia 17. Wiesbaden.

Jones, C. E. and Stolper, M. W. 1986. ‘Two Late Elamite tablets at Yale.’ In de Meyer, L., Gasche, H. and Vallat, F. (eds.), Fragmenta historiae elamicae: mélanges offerts à M.-J. Steve. Paris: 243-254.

Lewis, D. M. 1977. Sparta and Persia. Lectures Delivered at the University of Cincinnati, Autumn 1976. Cincinnati Classical Studies n.s. 1. Leiden.

——. 1985. ‘Persians in Herodotus.’ In M. H. Jameson (ed.), The Greek Historians, Literature and History. Papers Presented to A.E. Raubitchek. Saratoga, CA: 101-117.

Pompeo, F. 2015. ‘I Greci a Persepoli. Alcune riflessioni sociolinguistiche sulle iscrizioni greche nel mondo iranico.’ In Consani, C. (ed.), Contatto interlinguistico fra presente e passato. Milan: 149-172.

——. 2017. ‘Towards a redefinition of “context” — Some remarks on methodology regarding historical sociolinguistics and texts of antiquity.’ Athens Journal of Philology 4: 9-16.

Rollinger, R. and Henkelman, W. F. M. 2009. ‘New observations on “Greeks” in the Achaemenid empire according to cuneiform texts from Babylonia and Persepolis.’ In Briant, P. and Chauveau, M. (eds.), Organisation des pouvoirs et contacts culturels dans les pays de l'empire achéménide. Actes du colloque organisé au Collège de France par la ‘Chaire d’histoire et civilisation du monde achéménide et de l’empire d'Alexandre’ et le ‘Réseau international d'études et de recherches achéménides’ (GDR 2538 CNRS), 9-10 novembre 2007. Persika 14. Paris: 331-351.

Root, M. C. 2008. ‘The legible image: how did seals and sealing matter in Persepolis?’ Ιn Briant, P., Henkelman, W. F. M. and Stolper, M. W. (eds.), L’archive des Fortifications de Persépolis. État des questions et perspectives de recherches. Actes du colloque organisé au Collège de France par la ‘Chaire d’histoire et civilisation du monde achéménide et de l’empire d’Alexandre’ et le ‘Réseau international d’études et de recherches achéménides’ (GDR 2538 CNRS), 3-4 novembre 2006. Persika 12. Paris: 87-148.

Rougemont, G. 2012. Inscriptions grecques d’Iran et d’Asie centrale, avec des contributions de Paul Bernard. Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum part II, vol. I.1. London.

Schmitt, R. 1989. ‘Ein altiranisches Flüssigkeitsmass: *mariš.’ In Heller, K., Panagl, O. and Tischler, J. (eds.), Indogermanica Europæa. Festschrift für Wolfgang Meid zum 60. Geburtstag am 12.11.1989. Grazer Linguistische Monographien 4. Graz: 301-315.

SEG = Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum. 1923- . Leiden. Also available online at https://scholarlyeditions.brill.com/sego/

Stolper, M. W. 1984. ‘The Neo-Babylonian text from the Persepolis Fortification.’ Journal of Near Eastern Studies 43: 299-310.

——. 2025. ‘The chronological boundaries of the Persepolis Fortification archive.’ In Goedegebuure, P. and Hazenbos, J. (eds.), Ḫattannaš: A Festschrift in Honor of Theo van den Hout. Studies in Ancient Cultures 5. Chicago: 387-415.

Stolper, M. W. and Tavernier, J. 2007. ‘From the Persepolis Fortification Archive Project, 1: an Old Persian administrative tablet from the Persepolis fortification.’ ARTA 2007.001, available online at http://www.achemenet.com/pdf/arta/2007.001-Stolper-Tavernier.pdf

Cite this entry:

Aperghis, G. G. and Zournatzi, A. 2025. 'Pārseh (Persepolis): The Greek tablet of the Persepolis Fortification archive.' In Mapping Ancient Cultural Encounters: Greeks in Iran ca. 550 BC - ca. AD 650. Online edition, preliminary draft release. Available at http://iranohellenica.eie.gr/content/catalogue/parseh-persepolis/documents/takt-e-jamsid/2059400181

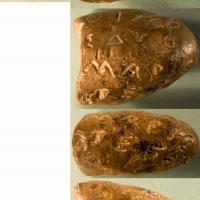

Clay tablet with record of an issue of wine inscribed in Greek. Persepolis Fortification archive. Taḵt-e Jamšid (lit. ‘Throne of Jamshid’), Pārseh (Persepolis), Fārs province, Iran. Ca. 500 BC. Excavations of E. Herzfeld (Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago), 1933. Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures (formerly, Oriental Institute) of the University of Chicago, Persepolis Fortification Archive Fort. 1771. Dim. ca. 0.035 X 0.03 X 0.02 m.